Before We Became Gods: Agency in Neoplatonic and Comparative Mysticism

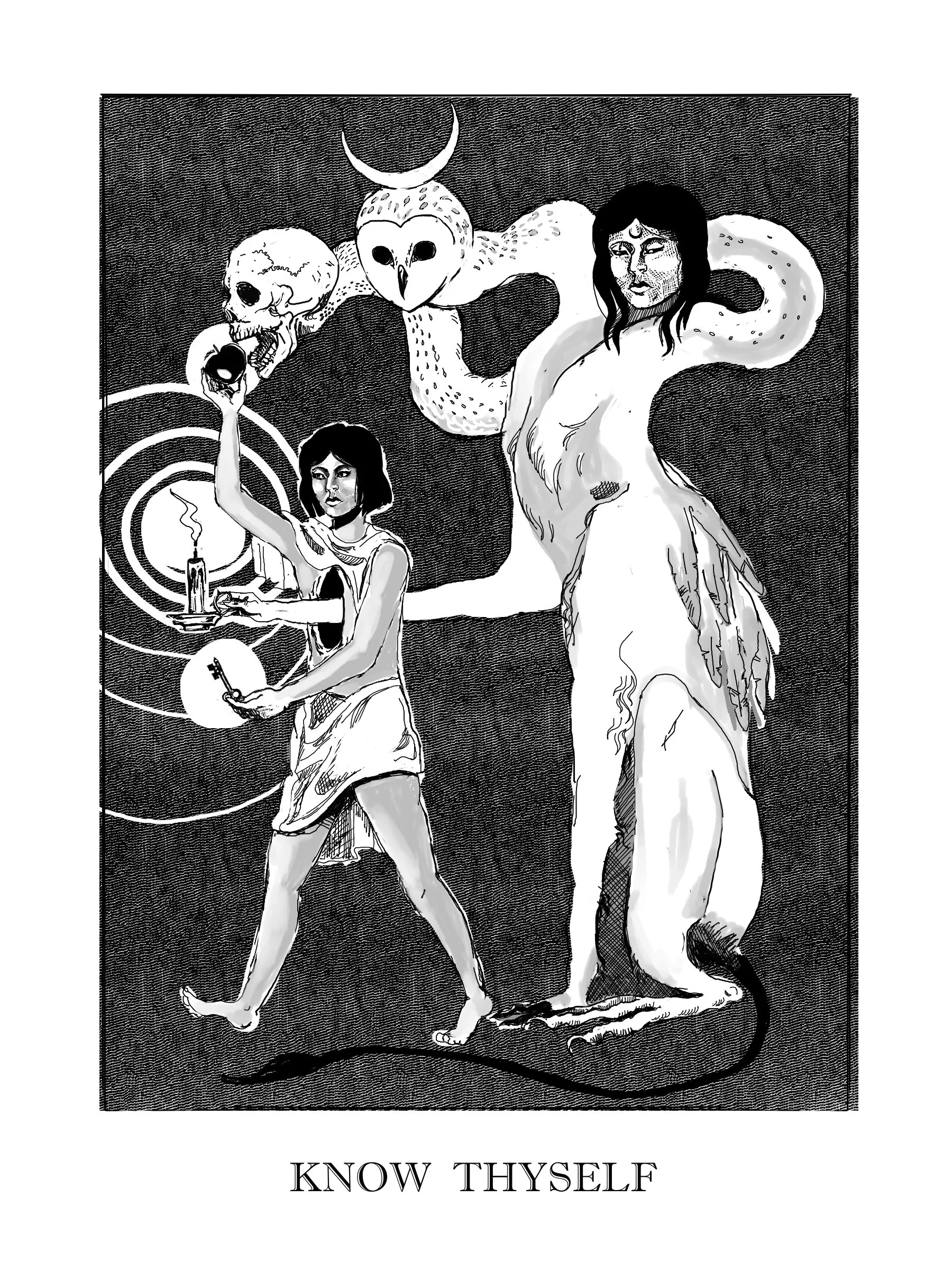

Authored by Daniella Penstak, Art by Kelsea Moors, & Edited by Georgina Rose.

Throughout history, humans have sought to explain why individuals appear drawn toward particular social roles and forms of meaning. Ancient metaphysical systems have hauntingly recognized these cosmic patterns as expressions of an overarching narrative and design, and even considered it as a bridge connecting us to the divine. Later on, these observations culminated into the creation of practices such as theurgy. We came to recognize divinity as our natural birthright and through the generations have reached forward into comprehending the divine.

Aligned toward metaphysical transformation, the philosophy of Neoplatonic theurgy was expanded to include ritual practices facilitating the soul’s ascent to the divine, determining that reason and ethical cultivation was, although still necessary for individual progress, ultimately insufficient. Foundational to this practice was acknowledging a hierarchical cosmos where a stratified ontological order provided a framework from where the practical process of spiritual ascent can be conceptualized. Theurgical rites were then intended to align the practitioner with the hierarchy itself, assisting with the ontological transformation of the soul. For instance, in On the Mysteries of the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and Assyrians (alternatively referred to as just “The Mysteries”) a work attributed to Iamblichus, ritual objectives are outlined to expedite the ascension process1. Examples include purifactory preparation, such as prolonged silence, fasting, and abstinence. Invocation of divine intermediaries was also done, namely the recitation of hymns and sacred names. Through these practices, as well as many others, the participant is reoriented towards the divine source.

At this point, the natural question arises as to what degree of free-will or agency do human beings possess in such practices. Can agency even be measured at all? The question of human free-will is notoriously a difficult one to pose given the profound implications asking it carries. The haze of ambiguity on this question, more recently fraught with indifference, does not persist because we originally chose to ignore it. Rather, it is the inevitable byproduct of our limited understanding and ignorance, a boundary imposed by the reach of our own capacity.

In modernity, the question of free-will has been pushed to the margins of dialogue and replaced by debates over corporate psychological manipulation, advertising, the influence of technology and social media, the rise of artificial intelligence, and increasing social isolation. In place of understanding human free-will, we have assumed the position of an all-knowing deity while succumbing to the trappings of social conditioning. Resulting from this is human dominion over artificial intelligence and technology without first comprehending our own role in the world. We have skipped a step, as we are not Gods, before we understand ourselves.

Understanding the Emanations of the Divine

Iamblichus is explicit that the contemplative methods of philosophy and intellect, grounded in human effort, are an insufficient means for divine union. Purely intellectual activity, he argues, does not cut it2.

From this, we can gather the essence of divine unity. The knowledge and application of symbols, those distinct signatures through which the different emanations of the divine are expressed, are what furthers one towards the divine. By entering into the presence of the Gods through the application of their proper symbols, the soul becomes receptive. Properly understanding these symbols and comprehending the differing emanations of the divine is the first step in actually undergoing this trying process.

There has been a process of dilution over the meaning of these emanations throughout modernity. However, through gathering from historical religious sources, one can piece together a colorful tapestry illustrating the network of divinity. Primary emanations, which are ontological principles rather than vague notions of our basic nature, are cast downward through a hierarchical system of existence, some of which are fundamental aspects of our existence. These emanations manifest in various ways, including behavioral patterns coloring our species and universe, such as the basic principle of cosmic order, human intellect, desire for love, fear of death, and so forth. However, flowing further from these higher principles are sensory manifestations. In other words, at the lowest level of existence, these divine emanations appear as symbols embedded in matter. The chambered nautilus shell associated with the Golden Ratio, the clear illumination of soft morning sunlight, the fear-inducing metallic scent of blood, or the gentle curvature of a coiling snake; all serve as physical expressions of these archetypal patterns. Historically, divinities were assigned to express these forms. What typically comes to mind today is the Ancient Greek pantheon. Others more well versed in ancient religions may consider even older traditions, including Ancient Egyptian or even Babylonian deities.

There is no formal method to assign deities to these archetypal forms. Although there are various schools of thought explaining the process from which one may gather meaning from observing specific pantheons, the path to spiritual evolution and unification with the divine is an intimate and personal experience. In The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Carl Jung explained how these archetypal forms, albeit largely unconscious, are spontaneously manifested in the psyche3. Perhaps from his assertion we can extrapolate a deeper meaning. Although in theurgical tradition the divinities are not usually considered “unconscious” or latent forms, regardless of what one’s perspective is on the matter, the process of manifestation is all the same. The secondary Jungian archetypal forms, such as the Trickster, the King, or the Maiden, are all universal patterns embedded in our world. Likewise, heroic gods like Thor, Horus, Indra, and Ares are all mythic personifications of the young and masculine “hero” and “warrior” archetype or divine emanation. The powerful Enlil and Anu are no doubt early personifications of the “king” form. Listing out the many divinities used to personify the “mother” form is truly ceaseless and would take a large portion of this essay. Needless to say, examples of this phenomenon are endless. With their intuitive wisdom, the ancients recognized these cosmic patterns and articulated them expertly through the method of personification using culturally specific applications.

Divine Destiny: How a Predetermined Reality is Painted in Historical Religions

In Genesis 15, Abram prepares a ritual with the expectation of entering into a covenant with the divinity Jehovah. This ritual, known in Hebrew as the “covenant of the pieces”, was a

well-established practice in the ancient Near East for formalizing binding agreements. It involved cutting various sacrificial animals into pieces where both parties were expected to pass through. This served as a visual symbolic oath. Jehovah promises Abram that once the covenant is fulfilled, he will be promised land and a future nation emerging from his line. Although both parties must participate in this ritual for it to be binding, the passage describes Jehovah passing through the parts alone in the form of a flame.

“When the sun had gone down and it was dark, behold, a smoking fire pot and a flaming torch passed between these pieces.” – Genesis 15:17

Abram’s absence from the ritual act of passing through the pieces suggests a symbolic emphasis on a destiny established independently of human action. In fact, this theme of predetermined outcomes appears consistently throughout the Old Testament. In the Book of Exodus, God declares in advance that Pharaoh’s heart will be hardened to Moses, ensuring that a divine purpose is fulfilled, despite Pharaoh’s choices (Exod. 4:21; 7:3).

The tragedy of Oedipus demonstrates a similar view of reality. Before Oedipus is born, the Gods deliver a prophecy declaring that he will kill his father and marry his mother. His parents, King Laius and Queen Jocasta of Thebes, try to escape this fate by abandoning their infant son. The child miraculously survives and is raised by another royal family in Corinth, unaware of his true identity. As the years progress, Oedipus learns of the prophecy himself. Mistakenly believing the Corinthian rulers to be his real parents, he flees Corinth to prevent the prophecy from being fulfilled. On his journey to the outskirts of the city, he kills a stranger in a moment of passion who also happens to be his biological father. Later, he saves Thebes by solving the Sphinx’s riddle and is rewarded with the throne and marriage to the widowed queen who is his biological mother, Jocasta. Years later, the agents of Apollo, namely the blind prophet Tiresias, reveal the reality of his past. When Oedipus finally understands what he has done, Jocasta kills herself and Oedipus is exiled.

The tale of Karna follows the life of a man born into an accursed fate, despite carrying a noble disposition. Born to an unmarried girl fearing social disgrace, Karna is abandoned as an infant. He is set adrift in a basket on the Ganges River where he is found and adopted by Radha and Adhiratha Nandana, members of the Suta caste serving under king Dhritarashtra. Despite being the son of the sun deity Surya, Karna matured unaware of his divine lineage. Though honorable, Karna is continuously humiliated for his low-status and is burdened by multiple curses that would eventually seal his fate. Later on, Karna discovers the nature of his birth and is even given the offer of kingship by Krishna on the condition that he changes sides in the Kurukshetra war, deeming him no better than a turncoat. Karna immediately refuses the offer, exhibiting his value of loyalty over power or recognition. However, as the story progresses, it seems that regardless of what decision Karna would have made, his life would be fettered by the constraints of Dharma. Engaging in direct combat with his half-brother Arjuna, son of the divinity Indra, previous curses waged against Karna are fulfilled rendering him powerless in battle. Krishna once again steps in during this pivotal moment, and urges Arjuna to prepare the final blow and end Karna’s life. Arjuna slays Karna by decapitating him using a celestial weapon.

Karna’s story expertly illustrates a picture of a determined destiny. It shows how even through one’s quest for honor and justice, Dharma cannot be ignored. More importantly, it reveals how the divinities selectively intervene to ensure one’s true destiny unfolds. In Karna’s final moments, Krisha urges for Karna’s death not out of malicious intent, but to finally fulfill the Dharmic role of Karna’s life. Similarly, the story of Oedipus demonstrates how divine prophecy is unavoidable, regardless how hard one tries to escape it. Lastly, Abram’s covenant with Jehovah exemplifies the self-assertive power of the divine in procedures where the inquirer may seek divine union and promise. It must be noted that these are just a mere three myths out of a great multitude explaining the cosmic role of the divine in either the theurgical methods of outreach or simply living one’s life according to their cosmic role.

Are we then to assume that human agency has simply never been an aspect of the theurgical process? Not necessarily. These examples are intended to paint a broader picture of how this operation functions. Too often, does humanity place itself above the mystery of life and grants itself ultimate control. We have forgotten the proper role of the divine and the role of the archetypal nature we individually possess. We are not separate from this reality.

Knowing the Self is Key

As previously discussed, the archetypal emanations of the divine are physically manifested and thoughtfully articulated in the cosmic order. Historically, identifying these emanations was best expressed through the emergence of specific pantheons and cultural traditions. However, due the nature of modernity, the action of admitting oneself to archetypal meaning is largely lost to time. ‘Modern’ religions have prescribed a unifying figure to encapsulate the outflows of the divine, typifying the “Christ figure” archetype. Jung described this mythic character under many names; Logos, Son of the Father, Rex Gloriae, Judex Mundi, Redeemer, and Jesus Christ Himself as the Godhead acting as an all-embracing divine totality. Other examples of this trend of monotheism can also include Atenism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Islam, and others. This is not to suggest monotheistic traditions are wrong. These methods of simplifying the divine were proven productive in the creation of civilizations and cultures. However, it is also true that these methods of religious simplification can also lose sight of important details in the unification process.

The emergence of various personality assessment tools over the years, such as the Myers-Briggs test, the OCEAN test, the Enneagram test, and many others pose the academic assertion that individuals are born with easily calculated behavioral archetypes. Although these assessments are accurate in understanding there are archetypes, they are inept at providing a holistic picture as many of them miss the mark on ignoring the metaphysical aspect in developing one’s identity. However, sufficiently drawing from the perspectives of Carl Jung, the discipline of personality psychology, behavioral genetics, and the decisions sciences, modern academia has at least started on the road toward fully understanding latent symbolic patterns of our universe.

Now that we have established the reality of archetypal divine emanations, cosmic order, and even analyzed the pattern of divine intervention through the analysis of various religious myths, the question arises again as to how significant human agency is in the theurgical process. Sadly, there is truly no way to know exactly what occurs first; whether the human notably decides to take the first step, or if the divinity calls upon their subject. What one can gather is recognizing the practical process of how this occurs. First, the archetypes must be understood as conduits through which the soul can ascend towards the divine. This is a fairly obvious point for anyone aware of theurgy. Second, and more important, is to understand how to accurately identify the process actually occurring.

How does someone know how to do Step 2? It is by realizing the true nature of one’s identity. Identity is not only limited to your genetic lineage or psychological makeup. Identity involves additional elements of specialized intrigue, desires, and serendipitous moments in life.

Knowing the Self is Key.

In modernity, we have forgotten how to correspond with ourselves internally. Young children are very clear on their likes and dislikes given they feel safe enough to express themselves and are not constantly exposed to external stimuli (namely, the Internet). In these conditions, very quickly will you discover that even a child understands themselves intimately. Certain symbols may intrigue them. They are direct about their desires and passions and, most importantly, are drawn to specific archetypes. Emanations of the divine will attract them and align with their latent structure of personality and identity.

Union with the divine should not be viewed as a complicated symbolic procedure alone. It is a participatory alignment wherein a practitioner actualizes latent divine attributes already present within their archetypal structure from the moment they are born. These latent attributes were first given to us by destiny, fate, or even the Divine. Theurgy, therefore, functions as a confirmation of an innate metaphysical relationship between personality, archetype, and personal divinity. Ancient peoples intuitively recognized the cosmic structure of our world and created myths, deities, and symbols to illustrate it. Deriving externally was the process we understood the divine in the past. Today, we are at the next step: recognizing it from within ourselves.

1 Taylor, Thomas. Iamblichus on the Mysteries of the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and Assyrians. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015.

2 Todd C. Krulak, “ΘϒΣΙΑ and THEURGY: SACRIFICIAL THEORY in FOURTH- and FIFTH-CENTURY PLATONISM,” The Classical Quarterly 64, no. 1 (April 16, 2014): 353–82,

https://doi.org/10.1017/s0009838813000530.

3 Carl Gustav Jung, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (Princeton, Nj: Princeton University Press, 1968).